Oil Tanker Ships Explained: Types, Sizes, Design, and Safety

- Dushyant Bisht

- 7 minutes ago

- 13 min read

Key Takeaways

Oil tankers carry crude oil or refined products in large built-in tanks, not containers.

Crude tankers usually move one cargo type on long routes; product tankers often carry many grades at once.

Tanker size classes (Aframax, Suezmax, VLCC, ULCC) affect cost, route options, and port access.

Key onboard systems include cargo pumps, piping, ballast tanks, and gas control equipment.

Double-hull ships and inert gas systems greatly reduce spill and explosion risks.

Strong regulations and inspections help ensure safe operations from loading to discharge.

An oil tanker ship is a specialized cargo ship designed to transport crude oil or refined petroleum products in bulk using segregated cargo tanks and advanced safety systems. These ships form the backbone of global energy logistics, moving approximately 2 billion tons of crude oil and petroleum products annually across the world's oceans [1]. Unlike standard cargo ships that carry containers or dry bulk commodities, oil tankers are purpose-built with sophisticated pumping systems, specialized hull designs, and stringent safety protocols to handle volatile liquid petroleum cargoes safely and efficiently.

Understanding oil tankers requires grasping the critical distinction between crude tankers that carry unrefined oil from production regions to refineries, and product tankers that transport refined petroleum products like gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel from refineries to distribution terminals. This fundamental difference shapes everything from ship design and size selection to operational procedures and regulatory compliance.

Whether you're researching energy supply chains, studying maritime logistics, or exploring how global petroleum markets function, comprehending how these specialized ships work provides essential insight into modern energy infrastructure.

What Is an Oil Tanker Ship?

Oil tankers transport petroleum in liquid bulk form, carrying cargo in multiple segregated tanks built directly into the ship's hull structure rather than in containers or barrels. This tank ship design allows efficient movement of enormous petroleum volumes, with the largest tankers capable of carrying over 2 million barrels of crude oil in a single voyage.

The fundamental architecture differs dramatically from standard cargo ships because petroleum requires specialized handling systems including cargo pumps that can load and discharge hundreds of thousands of tons of liquid, intricate piping networks connecting individual tanks to deck manifolds, heating coils for heavy crude oils that solidify at low temperatures, and sophisticated ventilation and gas management systems to prevent explosive atmospheres [2].

The industry measures tanker capacity in deadweight tonnage, abbreviated DWT, which represents the total weight of cargo, fuel, water, stores, and crew that a ship can safely carry when loaded to its maximum draft. For tankers, DWT provides a more meaningful capacity measure than simple cargo volume because petroleum products have varying densities. A ship with 100,000 DWT capacity might carry roughly 700,000 to 750,000 barrels of crude oil, though this varies with specific gravity and loading conditions.

Global petroleum logistics depends entirely on these specialized ships. Crude oil tankers create the critical link between producing regions like the Middle East, West Africa, and the Americas and the refineries that process crude into usable products. Product tankers then distribute refined gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other petroleum products from refineries to consumption markets worldwide. Without this maritime transportation infrastructure, regional petroleum shortages and surpluses would make modern energy markets impossible to sustain.

Main Types of Oil Tankers

The tanker fleet is divided into distinct categories based on cargo type and operational profile, with each serving specific roles in petroleum supply chains.

Crude oil tankers

Carry unrefined crude oil from oil fields and loading terminals to refineries.

Mostly operate on long-distance routes linking major producing regions to refining hubs.

Common routes include:

Middle East → Asia

West Africa → Europe

Americas → Pacific markets

Often built in larger sizes because bigger ships reduce transport cost per barrel on long routes.

VLCCs (Very Large Crude Carriers) are widely used on major crude routes due to capacity of 2 million barrels or more.

Usually have simpler cargo handling because they often carry one grade of crude instead of multiple products.

Product tankers

Carry refined petroleum products such as gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, heating oil, and other distillates.

Move products from refineries to distribution terminals and end-use markets.

Known for multi-grade cargo capability (can carry 6–8 different products in separate tanks).

Cargo tanks must stay isolated to prevent mixing and contamination.

Two main categories:

Clean product tankers: carry high-value products (gasoline, jet fuel)

Dirty product tankers: carry heavier products (fuel oil)

Switching from dirty to clean service requires deep tank cleaning and gas-freeing.

Generally smaller than crude tankers because they serve regional and multi-port distribution networks.

Shuttle tankers

Designed for loading crude oil from offshore oil fields.

Use dynamic positioning systems (computer-controlled thrusters) to hold position without anchoring.

Can load directly from floating platforms or offshore terminals in open sea conditions.

Used especially in harsh offshore regions like the North Sea and offshore Brazil.

Oil Tanker Size Classes (Aframax to ULCC)

The tanker industry categorizes ships into standard size classes based on deadweight tonnage capacity. These classifications originated from practical constraints like canal dimensions and port depths, but they've become the universal language of tanker chartering and operations.

Size Class | Approximate DWT Range | Typical Cargo Capacity | Typical Use | Key Constraints |

Aframax | 80,000–120,000 DWT | Approximately 700,000 barrels | Regional crude and product trades; maximum size for many ports | Draft restrictions at many terminals; flexibility for diverse routes |

Suezmax | 120,000–200,000 DWT | Approximately 1,000,000 barrels | Long-haul crude; maximum size for laden Suez Canal transit | Suez Canal draft limits; moderate terminal access |

VLCC (Very Large Crude Carrier) | 200,000–320,000 DWT | Approximately 2,000,000 barrels | Major crude routes (Middle East to Asia, West Africa to US Gulf) | Requires deep-water terminals; cannot transit Suez or Panama when laden |

ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carrier) | 320,000–550,000 DWT | Approximately 3,500,000+ barrels | Extremely long-haul crude (historically; few remain in service) | Extremely limited terminal access; only viable for specific long-haul routes |

Understanding why size matters requires recognizing the competing factors that drive tanker selection. Larger ships achieve better economies of scale because they move more barrels per voyage while requiring only marginally larger crew and incremental operating costs compared to smaller tonnage. A VLCC carrying 2 million barrels operates with roughly the same crew size as an Aframax carrying 700,000 barrels, making the per-barrel transportation cost significantly lower on the larger ship.

However, this scale advantage only materializes if adequate cargo volumes exist to fill the ship and if both loading and discharge terminals can accommodate the ship's size and draft requirements [3].

Port draft limitations constrain which size class can access specific terminals. Draft measures how deep a ship sits in the water when loaded, with larger tankers requiring deeper water. Many regional ports and terminals can only accommodate ships drawing 12 to 14 meters, limiting them to Aframax or smaller tonnage. Suezmax tankers can transit the Suez Canal when fully loaded, but VLCCs must either transit in ballast or partially loaded, making them unsuitable for routes requiring canal passage with full cargo.

Canal and chokepoint constraints shaped several size class definitions. Suezmax represents the maximum size that can transit the Suez Canal fully loaded under normal conditions, making this class ideal for routes from the Arabian Gulf or Red Sea to Europe where canal transit saves thousands of miles compared to rounding Africa. Economic considerations balance efficiency against flexibility.

VLCCs dominate high-volume point-to-point crude movements from the Middle East to Asia because they minimize per-barrel transportation costs on these major routes. However, Aframax and Suezmax ships command significant portions of global tanker trade because their flexibility to access hundreds of ports worldwide makes them suitable for diverse trading patterns.

From the Helm: "Many people assume bigger always means better in tanker operations, but commercial reality is more nuanced. A VLCC carrying 2 million barrels looks impressive, but it can only discharge at a handful of terminals worldwide with sufficient draft and storage capacity. Meanwhile, a medium-sized Aframax can access hundreds of ports globally, providing operational flexibility that often commands premium charter rates despite moving less cargo per voyage. Understanding which size class fits which trade pattern is fundamental to tanker economics."

Anatomy of an Oil Tanker: Key Systems and Components

Oil tanker design centers on safely containing and handling enormous volumes of volatile petroleum products while maintaining ship stability and preventing environmental contamination.

Cargo tanks form the core of tanker architecture, with the ship's hull divided into multiple separate compartments that isolate different cargo grades and provide structural integrity. Modern tankers typically feature 10 to 16 individual cargo tanks arranged in a centerline configuration with port and starboard wing tanks. Each tank is a sealed steel compartment capable of holding thousands of cubic meters of petroleum. Segregation between tanks prevents different cargo grades from mixing, critical for product tankers that might simultaneously carry premium gasoline in some tanks and lower-grade fuel oil in others.

Tank coatings protect steel surfaces from corrosion while preventing cargo contamination, with different coating systems specified for crude service versus clean product carriage [2].

Cargo pumps, piping, and manifolds enable loading and discharging operations that can transfer hundreds of thousands of tons of petroleum in 24 to 36 hours. Cargo pumps typically located in a dedicated pump room move petroleum from tanks through a network of pipes to deck manifolds where shore connections attach during port operations.

The manifold serves as the interface point where the ship's cargo system connects to terminal loading arms or hoses. Stripping systems ensure tanks can be discharged as completely as possible, minimizing cargo residue that represents both economic loss and potential environmental contamination. Modern pumping systems can discharge a fully loaded VLCC in approximately 24 hours when connected to terminals with adequate receiving capacity [2].

Ballast systems maintain ship stability and proper trim when sailing without cargo. A loaded tanker sits low in the water with cargo weight providing stability, but an empty tanker would be dangerously top-heavy and difficult to control. Segregated ballast tanks, separate from cargo tanks, hold seawater that provides weight and stability during ballast voyages.

International regulations require modern tankers to maintain segregated ballast, meaning ballast water never contacts cargo tanks, preventing the historical practice of using cargo tanks for ballast which led to oil pollution when ballast was discharged at sea [1].

Inert Gas Systems represent critical safety equipment that reduces explosion risk by replacing oxygen in cargo tanks with inert gas, typically cleaned exhaust from the ship's main engine. Petroleum vapors mixed with air in certain concentrations create explosive atmospheres, particularly during loading operations when tanks are partially empty.

The IGS maintains tank atmospheres below oxygen levels that would support combustion, providing an essential safety barrier against tank explosions. During cargo operations, the IGS continuously supplies inert gas to maintain safe conditions as petroleum vapors evolve from the cargo [2].

Safety and Environmental Protection

Oil tanker safety evolved dramatically following major maritime disasters, with regulatory frameworks and industry practices now emphasizing multiple protective barriers against spills and accidents.

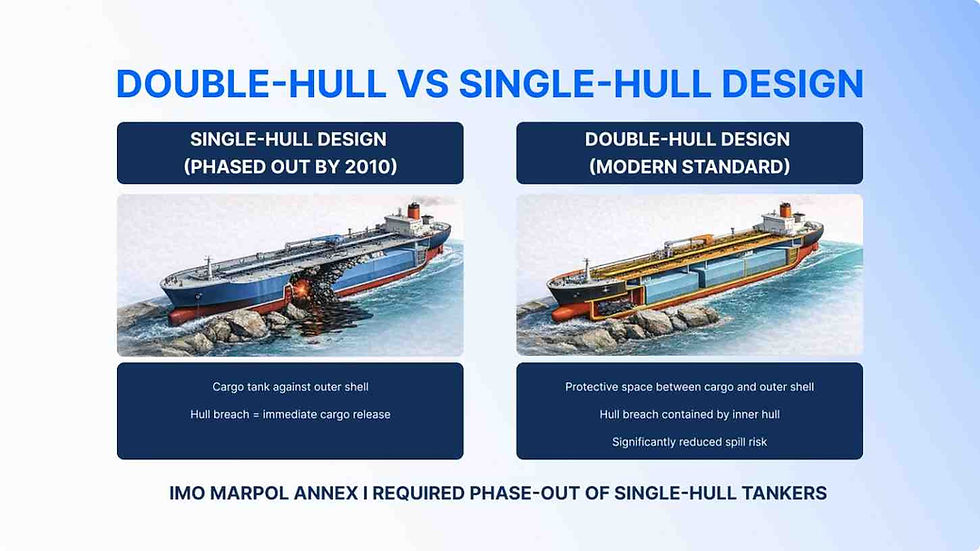

Double-hull design provides a secondary containment barrier that significantly reduces oil spill risk if the ship's outer hull is damaged by grounding or collision. The double-hull configuration positions cargo tanks several meters inboard from the ship's outer shell plating, with the space between serving as ballast tanks or void spaces. If the outer hull breaches during an accident, the inner hull maintains cargo containment, preventing or minimizing petroleum release to the environment.

The International Maritime Organization phased out single-hull tankers through MARPOL Annex I amendments that established increasingly restrictive age limits, with the final single-hull ships exiting service by 2010. This regulatory evolution followed major incidents like the Exxon Valdez spill that demonstrated single-hull vulnerability [1].

The double-hull requirement fundamentally changed tanker construction and operations, increasing building costs but providing substantial environmental protection benefits. Modern double-hull tankers demonstrate significantly lower spill rates in grounding and collision incidents compared to their single-hull predecessors, validating the effectiveness of this design mandate.

Vetting, inspections, and OCIMF SIRE create industry-driven quality assurance that goes beyond minimum regulatory compliance. Vetting describes the process where oil companies and charterers evaluate tankers before engaging them for cargo transportation, examining safety management systems, crew competency, maintenance standards, and operational history.

The Oil Companies International Marine Forum developed the Ship Inspection Report Programme, known as SIRE, which provides a standardized framework for tanker inspections conducted by trained inspectors representing major oil companies. SIRE inspection reports become part of a ship's permanent record, accessible to potential charterers who use this information to make informed decisions about ship quality and reliability [4].

The vetting process creates powerful economic incentives for tanker operators to maintain high standards because ships that fail to meet charterer expectations lose access to cargo, directly impacting revenue and asset values. This market-driven quality assurance complements regulatory oversight, often establishing performance standards that exceed minimum legal requirements.

How Oil Tanker Operations Work (From Loading to Discharge)

Oil tanker commercial cycles follow a consistent operational pattern regardless of size class or cargo type, with each voyage phase requiring careful planning and execution.

Pre-loading preparations ensure the ship is ready to receive cargo, with tanks inspected and verified suitable for the intended petroleum grade. For product tankers switching between different cargo types, this may require extensive tank cleaning to remove residues from previous cargoes.

Crew conducts ullage surveys measuring tank contents and confirming tanks are properly prepared. Shore and ship personnel coordinate detailed loading plans specifying which tanks receive cargo, loading sequences, and maximum filling levels.

Loading operations typically occur at specialized petroleum terminals equipped with pipeline infrastructure, storage facilities, and loading arms or hose systems.

The ship connects to terminal loading systems through deck manifolds, with multiple loading arms often used simultaneously to maximize transfer rates. Modern terminals can load large tankers at rates exceeding 10,000 cubic meters per hour. Throughout loading, crew continuously monitors tank levels, ship stability, stress on hull structure, and draft to ensure the ship remains within safe operating parameters. Ullage measurements track how much petroleum has been loaded into each tank [2].

Voyage operations present different considerations for laden versus ballast passages. Loaded tankers must manage cargo tank pressures and temperatures, particularly for heavy crude oils that may require heating to maintain pumpability. Weather routing services help identify optimal paths that minimize fuel consumption and avoid severe weather that could damage cargo or ship. Ballast voyages after cargo discharge focus on fuel efficiency while maintaining proper ship trim and stability.

Discharge and tank cleaning complete the voyage cycle, with procedures essentially reversing the loading process. Cargo pumps transfer petroleum from ship tanks to shore facilities, with stripping pumps removing residual cargo to maximize discharge efficiency. After discharge, product tankers often conduct tank cleaning operations, particularly when preparing to load different cargo grades.

Tank cleaning generates waste residues that must be properly managed according to environmental regulations, either processed through shipboard oily water treatment systems or delivered to shore reception facilities. Throughout all operations, safety zones and exclusion protocols protect personnel and prevent incidents. Petroleum terminals maintain strict hot work restrictions, smoking prohibitions, and electrical equipment controls to eliminate ignition sources.

The global petroleum supply chain depends absolutely on this maritime transportation infrastructure. Approximately one-third of all crude oil produced worldwide moves by tanker at some point between extraction and consumption [1]. Product tankers then distribute refined products to markets that may be thousands of miles from refineries.

This specialized shipping sector operates under intense regulatory scrutiny, significant commercial pressure, and constant public attention because the environmental and economic stakes of safe operations are so substantial. Understanding oil tankers provides insight into how global energy markets actually function. These ships aren't just transportation assets.

They represent critical infrastructure enabling the geographic separation between petroleum production, refining, and consumption that characterizes modern energy systems.

Conclusion

Oil tanker ships are built to move huge amounts of crude oil and refined fuels across oceans safely and efficiently. They are different from normal cargo ships because they use sealed cargo tanks, powerful pumps, and special systems to control flammable vapors. The tanker type and size depend on what is being carried and where it needs to go—large crude tankers serve major long-distance routes, while product tankers deliver many different fuels to regional ports.

Modern tankers also focus heavily on safety and environmental protection, with double-hull designs, segregated ballast tanks, and inert gas systems that lower the risk of spills and explosions. Strong rules from global regulators and strict inspection programs add another layer of control. From loading at terminals to discharging at ports, every step follows careful procedures. Overall, oil tankers are a key part of global energy supply, connecting production, refining, and everyday fuel use.

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute technical, operational, or regulatory compliance advice. Ship operations and maritime regulations vary by flag state, classification society requirements, and specific operational circumstances. Always consult with qualified marine surveyors, naval architects, classification societies, and maritime legal counsel for ship-specific guidance. Shipfinex is a regulated maritime asset tokenization platform and is not a classification society, marine engineering consultant, or ship operations advisor.

FAQS

What is the difference between a crude tanker and a product tanker?

Crude oil tankers transport unrefined petroleum from production regions to refineries, typically in large quantities using bigger ships like VLCCs. Product tankers transport refined petroleum products (gasoline, diesel, jet fuel) from refineries to distribution terminals, often carrying multiple different products simultaneously in segregated tanks.

What does VLCC mean in oil tankers?

VLCC stands for Very Large Crude Carrier, a size class of oil tanker with capacity between 200,000 and 320,000 deadweight tons, able to carry approximately 2 million barrels of crude oil. VLCCs dominate major long-haul crude routes from the Middle East to Asia.

Why do oil tankers have double hulls?

Double-hull design provides a secondary containment barrier that significantly reduces oil spill risk if the ship's outer hull is damaged by grounding or collision. The cargo tanks sit several meters inboard from the outer shell, so if the outer hull breaches, the inner hull maintains cargo containment. International regulations phased out single-hull tankers, with the final ships exiting service by 2010.

What is deadweight tonnage (DWT) and why does it matter?

Deadweight tonnage measures the total weight of cargo, fuel, water, stores, and crew a ship can safely carry when loaded to maximum draft. For tankers, DWT provides a more meaningful capacity measure than volume because petroleum products have varying densities. A 100,000 DWT tanker typically carries approximately 700,000 to 750,000 barrels of crude oil.

What is an inert gas system on an oil tanker?

An inert gas system reduces explosion risk by replacing oxygen in cargo tanks with inert gas (typically cleaned exhaust from the ship's engine). Petroleum vapors mixed with air in certain concentrations create explosive atmospheres. The IGS maintains tank atmospheres below oxygen levels that would support combustion, providing essential safety protection especially during loading operations.

What is the largest oil tanker size class?

ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carrier) represents the largest size class, with capacity from 320,000 to 550,000 deadweight tons, able to carry over 3.5 million barrels of crude oil. However, very few ULCCs remain in service today because their extreme size limits them to only a handful of terminals worldwide with sufficient depth and storage capacity.

What does Aframax, Suezmax mean?

These are standard industry size classifications based on deadweight tonnage. Aframax (80,000-120,000 DWT) was originally the largest size that could transit the Panama Canal. Suezmax (120,000-200,000 DWT) is the maximum size that can transit the Suez Canal when fully loaded. These classifications help standardize tanker chartering and operations globally.

Dushyant Bisht

Expert in Maritime Industry

Dushyant Bisht is a seasoned expert in the maritime industry, marketing and business with over a decade of hands-on experience. With a deep understanding of maritime operations and marketing strategies, Dushyant has a proven track record of navigating complex business landscapes and driving growth in the maritime sector.

Email: [email protected]

References

[1] International Maritime Organization. (2023). International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). Retrieved from https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL).aspx

[2] Wikipedia. (2024). Oil tanker. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_tanker

[3] Clarksons Research. (2023). Shipping Intelligence Network: Tanker fleet statistics. Retrieved from https://www.clarksons.com

[4] Oil Companies International Marine Forum (OCIMF). (2024). Ship Inspection Report Programme (SIRE). Retrieved from https://www.ocimf.org/sire